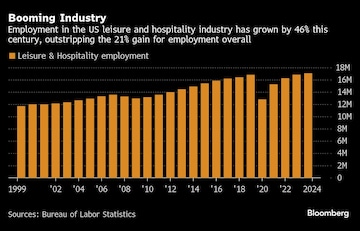

And yet, let’s not forget that a significant number of workers — around a quarter — have no access to paid holidays or vacation. Many of them are part-time and in the bottom 25% of earners, toiling in service occupations or working in leisure and hospitality.

Maybe this disparity in who gets paid time off is neither shocking nor upsetting. After all, jobs with lower wages and fewer benefits are often derided as “low skilled,” a catchall phrase to describe work that requires little formal education. It’s another way of saying that although such workers may get little in terms of benefits, it’s all they deserve.

Such thinking is short-sighted, and a lost opportunity for the economy to potentially build a new path to the middle class for millions of Americans.

Last year saw artificial intelligence crest across the economy. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. predicted that 1 in 10 businesses used AI in some way by the end of the year. It’s a trend that many workers fear will destroy jobs once thought to be safe, especially white collar ones that have been sources of growth and security. If AI can eliminate those types of jobs, where does that leave the rest?

In a time of uncertainty, the past has an indelible appeal. Tariffs to revive manufacturing, deportation to reverse immigration, traditional wives who take pride in not working (and who don’t take a job from a man) — each their own way of stepping backward, avoiding an unsure step forward.

Yet, many jobs with low wages and/or no paid time off are insulated from AI. Hotels could start using an AI chatbot instead of a concierge, but that chatbot can’t unload luggage from a car or deliver extra towels. Restaurants could use an iPad for ordering, but someone still needs to prepare the meal and deliver it to customers. Same for movie theaters, salons and spas, as well as the care economy, which includes child-care centers, nursing homes, hospices and hospitals.

It’s a bewitching thought to realize that these are the jobs that will always need a physical person to conduct, and yet policymakers have largely ignored them. Were policymakers to choose differently, they could take this “future proof” part of the labor market and possibly create a new pathway to the middle class.

For a long time, Americans have conflated good, middle-class jobs with manufacturing — employment that pays well but doesn’t require much formal education. Consider, though, that working on a factory line isn’t that far from busing tables at a restaurant, wheeling patients around a hospital or looking after children. It may be physical, but it’s often menial work. And yet one has health and retirement benefits, and the other doesn’t even get paid time off for a holiday.

To be clear, it’s not as if there’s a magic wand that can be waved that turns the service worker Cinderella into the middle-class princess. The output of a factory is more valuable in the economy than the output of certain services. Cars cost more than a meal, for example, which helps determine the wages of workers in the auto and restaurant industries. Also, many hallmarks of the middle class, like homeownership, are falling out of reach for reasons beyond wages. But policy can play a role, because that car can be built with the help of AI tools and fewer humans — or made elsewhere — but that restaurant isn’t going anywhere and will need people to prepare, serve and clean.

Think of this this way: If there were certainty that a job would be around in 25 years, a guarantee that it couldn’t be replaced with AI or outsourced to another country, how low quality should it be? Should it have paid holidays and paid vacation? Policymakers, staring at a set of jobs that both lack basic standards and yet will not go away, must decide.

And paid holidays and vacations aren’t the only concern, or even the top priority, given that a quarter of workers don’t even have paid sick days, three-quarters don’t have paid family leave, and that wage, hour and workplace safety enforcement agencies have fallow budgets, and the federal minimum wage is an embarrassing $7.25 an hour.

What to do? Update the Fair Labor Standards Act. It was originally established to set a minimum wage, overtime and prohibit child labor. Fair today means require accumulation of paid vacation, sick days and holidays while increasing the federal wage floor. At the same time, boost funding for enforcement of those laws. The cost to the government is nothing for the standards and trivial for the enforcement (current Wage and Hour funding is just over $2 billion). Paid family leave is a different beast — it’s more of a risk than a benefit and should thus be brought into a social insurance scheme, like Social Security.

Employers, especially small businesses, would no doubt claim such costs would be prohibitive. That may be true for some businesses, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that for employers that provide such benefits, paid holidays, vacations and sick days account for 3.5%, 2.2%, and 1% of total compensation costs. And two-thirds of businesses with fewer than 100 employees already provide paid holiday and vacations, and even more provide paid sick days.

Sure, there’s a cost but there’s a clear dividend: higher-quality jobs that are a permanent part of the economy. There’s no way to guarantee that today’s low-paid food server will be tomorrow’s middle class, but there is a way to guarantee that today’s low-paid food server will be tomorrow’s low-paid food server and that is for policymakers to do nothing. Don’t consider what these jobs were or what they are, but what they could be. Make policy for the future we know is coming, not the past.

[ad_1]

Source link