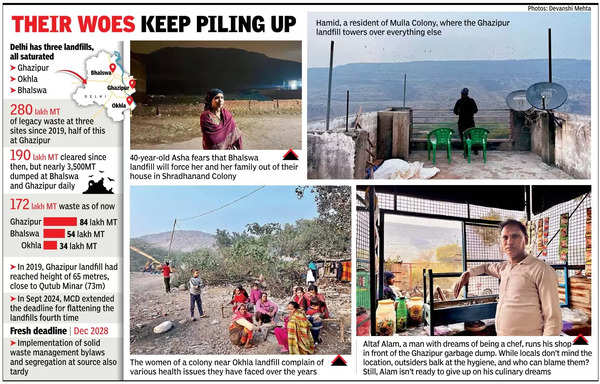

NEW DELHI: Hamid who lives in Mulla Colony in east Delhi, has a complex relationship with a mountain of waste adjacent to his house. “Every morning for 54 years, I’ve woken up to the most faithful neighbour,” he says. “Our garbage mountain.”

The quip about the Ghazipur landfill is not accompanied by a twinkle in his eyes. “It has watched me grow up from playing with marbles to now having breathing difficulties and I’ve watched it grow from a heap to a hill. I am still here, still hoping for a change, still voting. I am more stubborn than the landfill.”

Every election comes with hope for people like Hamid that their lives will change with the flattening of the towering landfills at Okhla, Bhalswa and Ghazipur. Every five years prove their hopes are in vain. As the Feb 5 polling approaches, the people, therefore, aren’t sure about what their votes will achieve.

In Okhla, the people are only grateful, if they can be in the situation, that the landfill is the smallest among the three overused dumps and farther from their residences than at the other two sites. The youngster appeared belligerent. Sanju, 18, who refused to register as a voter, said, “Our parents treated the voting booth like a temple, going there faithfully every election. But what did their devotion get them? My friends and I could vote, sure, but we’ve watched our parents play this game for years. Different faces, same promises, zero change.”

Older than Sanju but as frustrated, Shamu, 36, said resignedly, “Koode mein rehne wala koodewala ho jata hai…ab aadat ho gayi hai (Those who live near garbage themselves become like garbage. We are now used to the dirt).”

He went on, “While we understand that the city’s garbage needs a place for disposal and some of us are even fine with the landfill as long as it’s properly managed and doesn’t catch fire every summer, there are many other issues we simply can’t ignore now. Like the uncovered sewers or the shortage of public toilets.”

A cynical resident added,“The garbage attracts foraging wild pigs. These same pigs are slaughtered and sold by local butchers. Such is our life — we consume garbage through the meat, inhale the bad air and eat food on which the flies sit after first having sat on the waste material.”

At the Ghazipur landfill, it’s not just the toxic fumes that waft in every summer when the combustible gases catch fire. Residents also face a range of serious concerns far beyond breathing issues.

With one of the city’s biggest abattoirs located near the landfill there, tonnes of animal remains and waste are dumped, creating their own blend of insufferable stench and toxicity. At the spot where the Ghazipur Murga Mandi meets the mountain of muck, there are countless garbage trucks and thousands of birds of prey circling above.

The vultures and eagles line the rooftops, nest on electric towers and dive down to snatch scraps of carrionsfrom the landfill and poultry market. Zoologists warn that this environment, where animals coexisting with hazardous waste, can be a breeding ground for new diseases. The meat supplied to shops across the city largely comes from this market, rendering the situation even more of concern.

Mohammad Zulfkar of Mulla Colony said, “A few years ago, the mountain collapsed and claimed some lives. Every summer, when there are fires, people with asthma, likeme, are left on edge. The butcher’s market makes this place aliving hell. Unless someone addresses the root of the problem, which is the big garbage dump, nothing will change.”

Still voters here are hopeful, optimistic that their elected representatives will do something for them. Khairun Nisha, 64, said, “I’ve been voting for 36 years, and no matter how tall the landfill gets, the people here won’t lose hope. We may not always agree, but we’ll never stop paying at-tention. This year, we’ll choose wisely for whom to vote.”

At Bhalswa, people are more concerned about the roof over their heads than ballots. They live in dread about being displaced from their homes because there is no clear plan for the rehabilitation of long-term residents. People of Shraddhanand Colony worry that they’ll be forced out from the area because the landfill is steadily approaching and encroaching on their living space metre by metre.

Dr Surender Kumar said he saw young mothers and pregnant women dealing with long-term health issues every day. “Knowing what people here face, how can I cast my vote without feeling responsible for their well-being?” he asked.

Phoolchand Yadav sighed, “As a parent, I want to give my child the best education. But my son studies in the proximity of a garbage dump and breathes in poisons as do hundreds of other kids. I can’t afford a better school. There’s no way out.”

The leachate from the landfill makes the roads slippery. “Going to work, especially during monsoon, is a challenge — we constantly worry about slipping into the drain. It’s happened to several people already,” said Sangeeta, 40. Asha, also 40, added, “The water is undrinkable, salty and foul-smelling. For how can we live like this? Every morning when I wake up, I look at the same heap of garbage getting bigger and coming closer, it gets scary at night. It’s inhuman and yet we’re still expected to vote in the hope of change.”