Having written four successful books about the ascent of the East India Company on the back of a weakening Mughal Empire, William Dalrymple turns his attention to ancient and early medieval India to produce a powerful and sweeping account of a land that was once an economic powerhouse, a civilisational cradle and an exporter of merchandise and ideas — philosophical, religious and scientific. To read The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World is like opening a magic box — packed with strange and absorbing characters, quirky and almost-forgotten narratives, startling and uncommon facts. Once again, Dalrymple demonstrates that rare ability to use primary historical sources to make places and people come alive and show that it is possible to write about the past in a way that is at once consequential and extremely engaging. Excerpts from his first interview to an Indian publication:

It is a truism that authors write about subjects that interest them. But were you also driven by the urge to spread your wings, to be known as more than a historian of the East India Company?

No, not at all. When I was growing up, I was very much focused on prehistory. My first ever trip to London was to go to the Tutankhamen exhibition. I spent all my teenage holidays going to some archaeological excavation or the other. Before I discovered India, my whole life was archaeology and prehistory. When I first came to India in 1984, I was going around sites like Sanchi and Ajanta. So my teenage self would be very surprised that I ended up focussing most of my professional life on the 18th century, which is way later than anything I had been interested in as a kid.

One of the oldest Buddhist paintings in the world found in Ajanta, cave 10. This is Benoy K. Behl’s digitally restored photograph of the original.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

This came back to me very strongly just after I had begun writing The Anarchy. I went down to spend a weekend exploring Ajanta. There in caves 9 and 10 were these extraordinary pictures, which I had never seen before. It turned out that the ASI had cleaned up these two caves which have the earliest Buddhist paintings in existence. Most of Ajanta is about 650 CE. These are 150 BCE. What happened was the Nizam of Hyderabad, who then controlled Ajanta, had brought in some Italian conservators who cleaned and conserved them but then put on shellac varnish, which almost immediately attracted batshit. And within 10 years, the paintings in these caves had become completely obscured and not included in any of the books.

A mural of Bodhisattva Padmapani in Ajanta.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

The ASI, about 2014-15, cleaned these up without any fanfare. So I took six months off from The Anarchy to write a whole series of articles about them. First, a scholarly article in Marg and then more wide-ranging pieces in the Guardian and the New York Review of Books and other places. This because not only were they the oldest Buddhist paintings in the world, they were the oldest art since Bhimbetka. They are also the first portrait pictures, in a sense, of Indians. I realised that there was a history that people didn’t know very well. These early pictures are the seed from which wider Buddhist art rose as far away as Japan and eastern China. That is what kicked me off on this trail.

But surely you must have realised you were doing more than repositioning India as a sort of cultural and civilisational hub; that you were also repositioning yourself as a historian.

It was not a conscious decision. I was just pursuing stuff that interested me. My books take about five years. You have to be madly in love with the subject. And this was a subject that not only provided wonderful reading all the way through COVID, but also spectacular trips in Southeast Asia as well as all the early Buddhist sites in India.

You have stressed the importance of visiting places you write about. The book makes it clear that you travelled to Cambodia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Did you also travel in China?

I travelled a lot in China earlier….

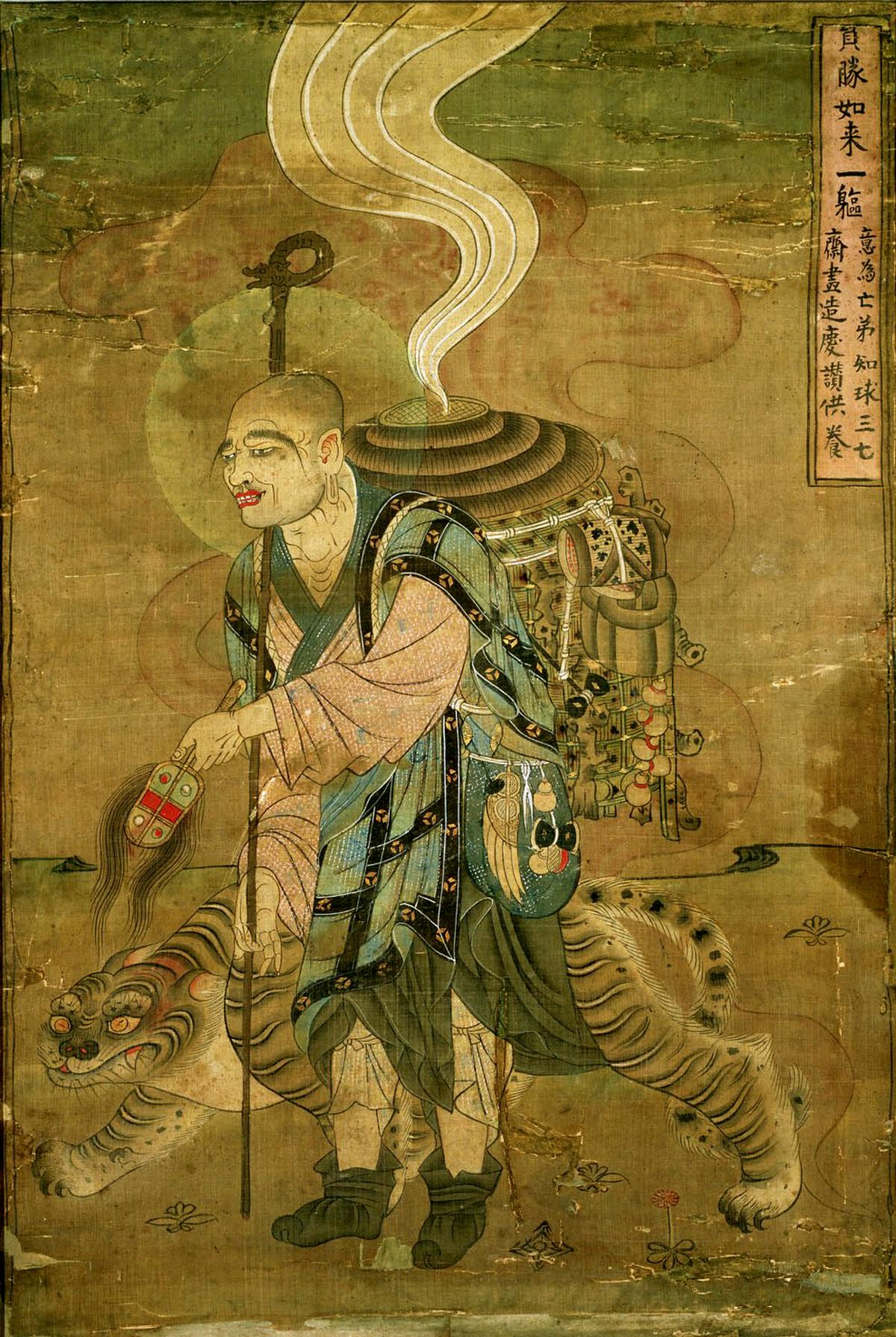

Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang in India.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For ‘In Xanadu’…

For In Xanadu, I followed pretty well the route that Xuanzang [the great Chinese Buddhist monk who came to Nalanda] took. It was one of the formative journeys of my life. I have been in and out of China quite a lot over the last few years. But I didn’t go back to eastern China for this book.

Empress Wu Zetian

| Photo Credit:

Getty images

You have traditionally adopted a narrative approach to writing history. And this is very much in evidence when you talk of Xuanzang and the Empress Wu Zetian. But overall, was it a challenge to deploy the same approach when writing about ancient India and the classical world? Were there areas where facts were easier to mine than stories?

Yes, I found there were sections of the books such as the one of the Kushans where you simply don’t know enough to paint a very full portrait of a king such as Kanishka. Some of the lesser ones such as Vima Takhto are very shadowy figures. On the other hand, there are figures that come shooting out of the sources, particularly in the Chinese chapters. In Xuanzang’s case, we not only have his own account but we have his letters and a contemporary biography. So, we can reconstruct his life, and this intersects very nicely with Wu Zetian, who knew Xuanzang and was very much an ally of him. The two were very much working in concert.

A statue of Xuanzang at a temple in Taiwan.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

So, in those two chapters, you have very closely focused sources, almost like the 18th century sources that I’ve been using for The Anarchy and The Last Mughal. There is also the chapter on the Barmakids [Buddhist priestly family of Iranian origin], who are also very well represented. Yes, there are chapters in the book such as the one on the Khmers where the characters are more shadowy, but overall there are some outstanding characters who come together on the page. There are enough biographical stories to satisfy the casual reader.

Buddhist monks visit Angkor Wat, in Siem Reap, Cambodia.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Some of the characters in ‘The Golden Road’ are not generally well known in India. Did you get a sense that you were writing a history that many Indians have forgotten? Or not cared to remember?

It isn’t only that the characters are not well known. I don’t think many Indians realise that Angkor Wat was a Vishnu temple. I spent a lot of time in Cambodia over the last five years. And you find Indian tourists astonished to find Kurukshetra and the battle of Lanka depicted on the walls. There is only a hazy recognition of quite how crucial India was in the formation of Southeast Asia. Wherever you go in Cambodia, you find stories that often are specifically linked to the area where one lives. Take Angkor Wat. There’s the Battle of Kurukshetra which is 100 miles north of where I live (Delhi). And then there are pictures of Krishna with the Gopis, which is 100 miles south in Mathura. And here they all are 5,000 miles to the east in the Mekong Delta.

Specialists know this and there’s a great deal of very fine Indian scholarship on this. But beyond the academic history departments and those that know that world, there’s very little in this book that will be familiar to many Indian readers beyond the basic starting points like the Buddha and Ashoka.

A statue of Al-Khwarizmi in Khiva, Uzbekistan.

| Photo Credit:

Getty images/istock

Hardly anyone has heard of Wu Zetian in India. The same is true of the Barmakids taking Indian Gupta mathematics to Baghdad. I don’t think people know that Al-Khwarizmi wrote a book on Hindu mathematics that gets into the hands of Fibonacci. These things are simply not well known.

There is in India a nationalistic sense of pride in ancient Indian science, which is very widespread. There is an understanding that India came up very early on with a lot of the big ideas in mathematics and astronomy. But the specifics of what exactly was new in Indian thought and what is Babylonian or Greek and the specifics of how these Indian ideas travelled and the extent to which they conquered a place like China is not known at all. I certainly didn’t know this when I started this trail.

Would it be fair to say that your book is made up of two somewhat separate but interconnected stories? There is the dissemination of Indian philosophical and religious ideas to China and Southeast Asia and mathematics to the Middle East. And then there is this other story which sort of predates this, which is really a trading relationship with Rome, and which lends itself to the title of your book ‘The Golden Road’. Tell us a little about how the two are interconnected.

I think it’s very much one story. This book is the story of how India had a much larger footprint in the world than even Indians realise. Yes, Indians are aware that there is this world of Indian science and maths that has not received due recognition. Westerners are simply unaware of this; they think Arabic numbers came from Arabia, full stop.

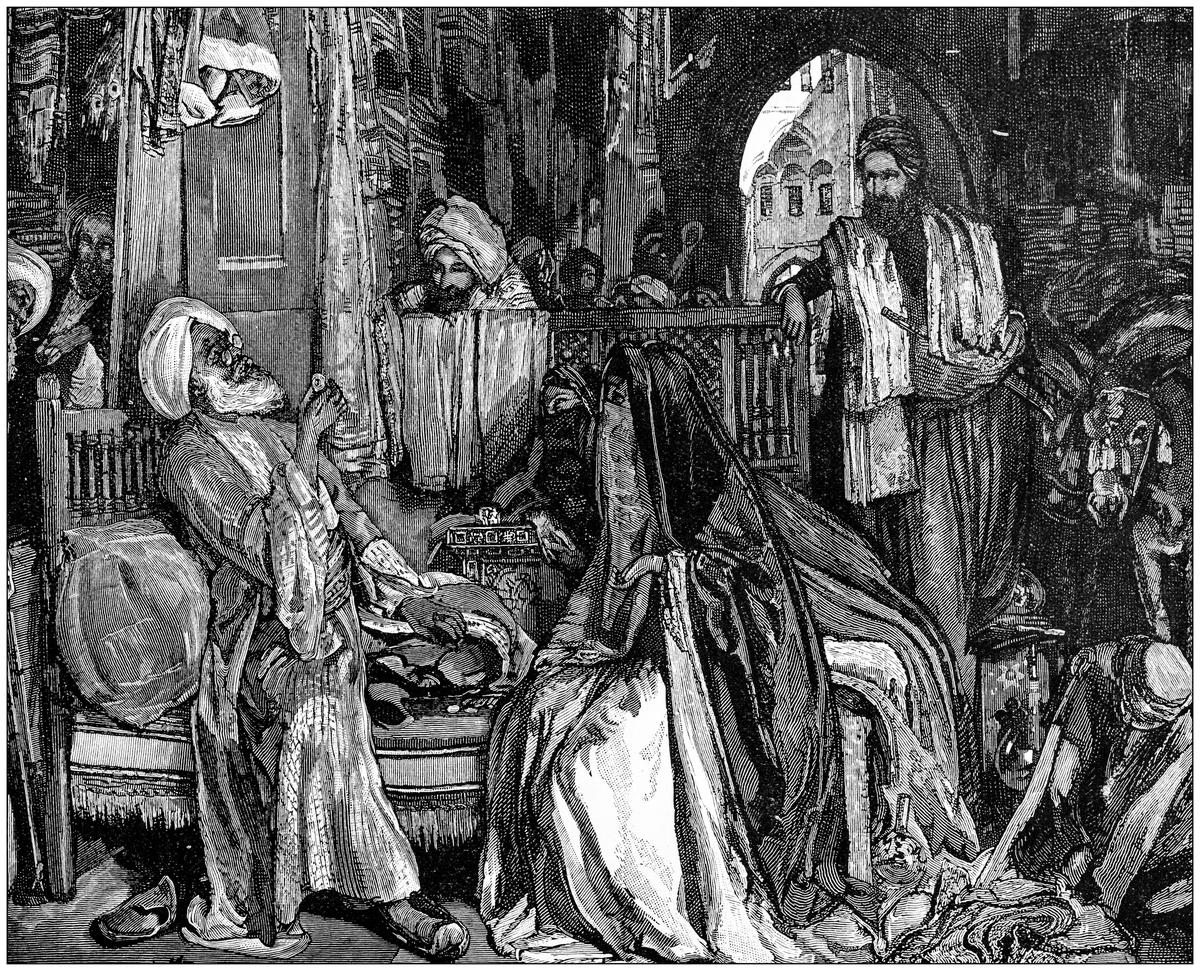

An antique painting of traders in West Asia.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

This is a story of how Indian trade led Indian ideas to spread around the world. There are two separate concepts in the book. One is the Golden Road and the other is the Indosphere. The first is the trade network which operates on the monsoon. And the fact that India is blessed with this wind system — which blows very fast in one direction for six months and then reverses and blows very fast back within the next six — has meant that it’s been very easy for Indian traders to put up a sail and travel to Persian Gulf or to the Red Sea on the one hand or to Java, Indonesia, the Mekong Delta and China on the other. And this has been a terrific advantage that India has had along with its harvests, its rich mineral resources, spices and ivory and gemstones.

Once the art of navigating the monsoon winds was understood, Indian merchants and in their wake Indian scholars, Brahmins, missionaries and so on travelled soon after. There is this very exciting new body of archaeological evidence which has emerged in the last 10 years about the extent to which India was the leading trading partner of Rome.

Illustration of a crowded oriental market at sunset.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStock

According to the latest edition of the Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy, a third of the Roman imperial budget was generated by customs taxes on the Red Sea coast. So, everything up to Hadrian’s wall, the Rhine frontier, the chain of forts across Algeria — a third of this is paid for by the import of silks, cotton, ivory and wild animals. This creates an enormous philosophical and historical impact in both directions. So, I’m pretty sure that monasticism which starts in the Buddhist world spreads to West Asia through this network. Recent finds of the Buddha in Berenike [in Egypt] back this up. It is an extraordinary mutual influence in both directions. We have the arrival of Christianity in India, the influence of Roman art on Gandhara and the way it alters Buddhist art. And then the Roman Empire collapses in the fourth century and India has to find an alternative source of wealth…

The facade of St. Thomas Church – the oldest church in India founded by Apostle Thomas in 52 AD – in Palayur, Thrissur district, Kerala.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

So, it looks eastwards…

Yes, and you get the beginning of large-scale Indian trade with Mekong Delta and Burma and Java in the fifth, sixth centuries and then the first temples get built. And these grow into the massive monuments in Borobudur and Angkor Wat. And so, these two concepts of the road (which is this maritime trade network based on the monsoon) and the Indosphere (which is the wider world of Indian ideas and art that followed these trade networks) are very closely related. I don’t think of them as two distinct bits of the book at all. I think the whole idea is that this was integrated and that ideas which have often been separated from each other such as the spread of Buddhism and the spread of Sanskrit and the spread of Indian science are all one process. They are part of one extraordinary diffusion of Indian culture which has meant that India is the base of so much of Asian but also world civilisation.

Prambanan ruins in East Java.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

Much of this dissemination was peaceful.

Exactly. That’s where I differ from the Greater India historians of the 1920s and 1930s who were very much of the idea that there were Hindu colonies, as R.C. Majumdar put it. Yes, there are moments of military activity by the Cholas in the 11th, 12th centuries. But it is overwhelmingly a peaceful diffusion of ideas like the diffusion of Greek ideas westwards.

No one forced the Romans to build in Greek styles or Scotsmen and Englishmen for that matter. It was the attractiveness of those ideas that led to so many little Parthenons turning up in places like Edinburgh, Sweden and Germany. In the same way, the shore temple at Mahabalipuram turns up in the highlands of Java. It isn’t because of conquest but because these are a wonderful architectural achievement which people want to emulate. I would argue that the book is not made up of two different parts. The idea is that they’re very closely integrated and that the Golden Road leads to the spread of the Indosphere.

What next?

I’ve just sold four more books to Bloomsbury. I’ve just completed a big book deal, which will keep me till I am 80 (laughs). I have got a whole series of ideas. One that I would love to do is a fifth company book around the opium wars. I have discovered a stash of family letters about this. My great grandfather, not on my Dalrymple side, but my maternal one, was an opium trader. And I have got a trunk of his letters dealing in China, which will be a very strong new element of the book. And it’s a shocking story. The extent to which opium trade enriched not only the East India Company, but many Indians who were involved it. The extraordinary violence and injustice of this monstrous corporation turning into the world’s largest narco operation makes Pablo Escobar look like Bananas in Pyjamas or Andy Pandy (laughs).

I also want to do a family history, particularly of my Franco-Bengali great grandmother Sophia who became a great muse to the pre-Raphaelites. She was the aunt of Virginia Woolf and was part of this whole world of early pre-Raphaelites.

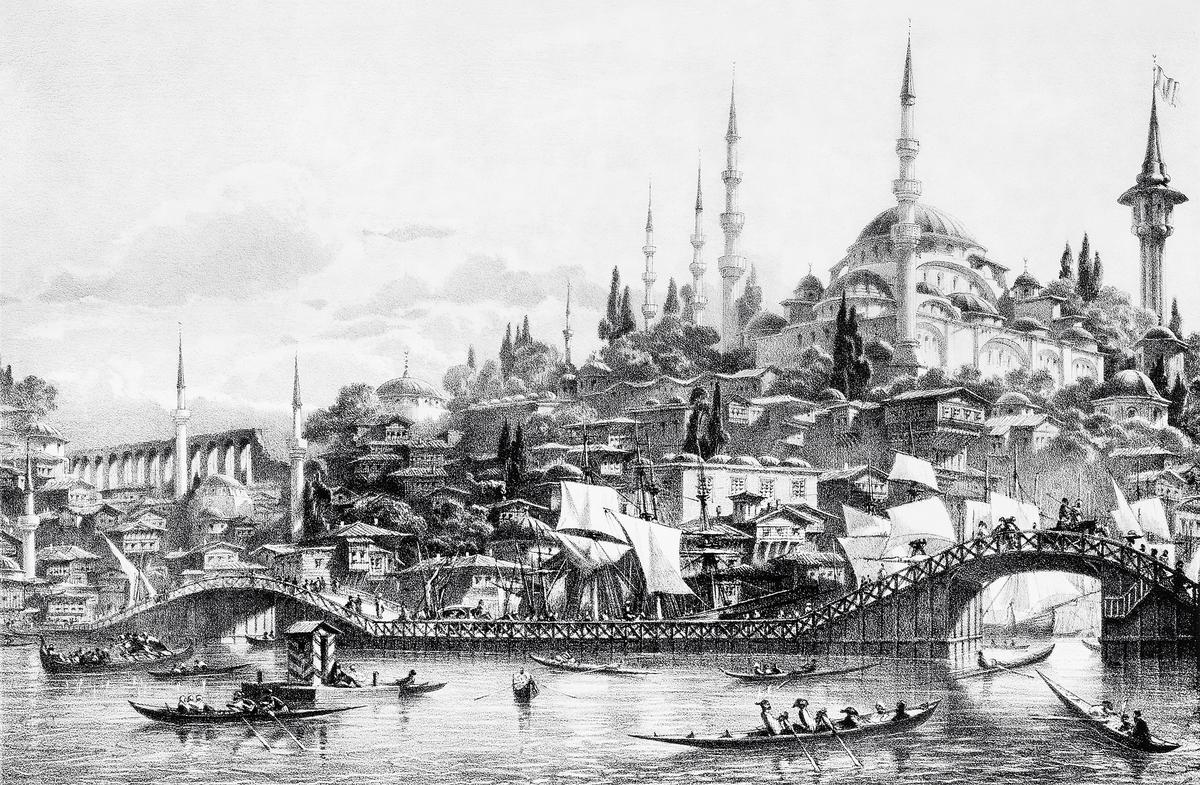

An engraving of Istanbul, Galata Bridge. Illustration from ‘Book of L’Orient’, dated 1839.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Then I want to do a sort of version of White Mughals but set in the Ottoman Empire, White Ottamans if you like. There was this extraordinary character Henry Hyde, who was a British Levant company trader who made a fortune importing currants to England from what’s now the Peloponnese [Greece]. These are some of the next projects.

The thing we haven’t talked about, the big change in my life, is the podcast. As you know, for a writer to sell 100,000 copies of the book is a major achievement. But the reach of the podcasts that people listen to — when walking the dog, jogging or stuck in traffic jams — is massive. And it creates a type of history that didn’t exist before. We’ve crossed a couple of months ago, 30 million downloads and we’ll be up at 40 million soon. It’s a whole new world and it shows up this huge appetite for history, which people can now access in a much more accessible way.

The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World; William Dalrymple, Bloomsbury, ₹999.

The interviewer teaches philosophy at Krea University and is the author of ‘The Great Flap of 1942’.

Published – September 05, 2024 09:03 am IST

[ad_1]

Source link